Accessibility with Emma Stone

Medical v. Social disability, disability confidence, invisible disabilities, living in an albe-ist world, sacrificing the universal path for the standard path

Emma is a behavioral scientist/ researcher/ strategist/ puzzler/ experience designer/ accessibility advocate who has a neuroscience degree from Harvard. She strives to connect with people holistically, understand behavior deeply, and solve complex problems creatively. Her primary method: ask a lot of questions and get hands on with a solution.

We would love to hear about your journey. How did you initially get into accessibility?

It really feels like a culmination of experiences happening around me, as opposed to one clear beginning. Early in my undergraduate experience, I was drawn by the intersection of behavioral science and design, which led me to focus on pursuing user experience design (UX). I was (and still am) excited about understanding an individual’s needs and motivations to better inform the way we design systems and products to promote desired behaviors and better experiences. Meanwhile, I was working in a research lab at Harvard Medical studying the effects of visual impairment on brain architecture and behavior, trying to understand interventions to support individuals recovering from eye diseases. I was also starting in a Designing for Disability course where I was matched with a “client” in the Cambridge community who had a design problem that needed to be addressed, and who also happened to have disability (in this case, my client was both legally blind and a wheelchair user). Amidst all this happening, my grandfather’s Parkinson’s Disease was escalating to a point where he could no longer operate certain machines, tools, and technology independently.

Throughout all of this, I came to realize how often products and services fail to consider the unique challenges and needs of people with disabilities. They don’t just have a poor user experience, in most cases they are entirely unusable or inaccessible. This frustration was what ignited my interest initially - there was a fundamental problem to be addressed. Then, soon thereafter came the exciting realization: I found that when inclusive and accessible design was applied and embraced from the start, it made experiences better for everyone -- this was the fuel that has kept me going.

How has the journey been since?

While at school, I continued to pursue roles and opportunities focused on accessibility. I joined the Harvard Libraries team as a digital accessibility researcher and designer. My primarily role was to evaluate the online library portal based on its accessibility and adherence to WCAG 2.0 guidelines. To be honest, it was tedious work. I would spend hours tabbing through screens, listening to the robotic voice descriptions of screen readers, and evaluating color contrast ratios of different icons. For some reason, it never really bothered me; it was still fulfilling. I have to think because part of me knew that my discovery was making a meaningful impact on part of the community’s library experience. After graduation, I joined an internal accelerator consultancy team within a massive healthcare company. My focus was on product experience design and strategy. It eventually became clear that our team was not as well versed in accessible design and best practices. Fortunately, our leadership team empowers us to bring our unique perspective to conversation and elevate the team. I conducted team trainings, initiated new accessibility practices, redesigned the templates we used for deliverables, and crafted our accessibility statement. Although I was the initial champion, each team member has taken it upon themselves to learn, apply, and commit to accessibility. Similarly, my learning is ongoing and evolving. At the beginning of this year, I got my certification in Accessibility Core Competencies (CPACC) so that I could continue to lead with an accessibility-first mindset.

What do you spend your time on these days? What’s top of mind?

I have zoomed out since my days of auditing every feature of a library portal. These, days I am focused on championing disability inclusion in the workplace, more generally. In other words, I strive to build awareness and drive engagement across our company by organizing speaking events with individuals from the community, conducting trainings, and promoting resources. I find that the two greatest barriers that keep us from moving forward around topics like disability and accessibility are lack of knowledge and fear, both of which are self-imposed barriers. People either have not realized the personal, societal, and business benefits or they are fearful that in trying to do the right thing, they will end up doing the wrong thing. People lack “disability confidence”, which means they cannot embrace best practices nor infuse accessibility into their strategy effectively. I am focused on shifting the mindset from thinking of accessibility as an compliance issue to embodying it as an organizational and cultural value. Only when we change the conversation and then normalize that conversation can we move toward sustainability and transformational change.

What has surprised you most about the discussion around accessibility?

What continues to surprise me are the sheer numbers of potential impact. For example, few realize that over 61 million adults in the US identify with having a disability - that’s close to 1 in 4 adults. Globally, 1 Billion people (or 15% of the world) are living with a disability, and 53% of people are touched by someone living with a disability. This amounts to a $8 trillion market considering the spending power of individuals with disabilities and their families, never mind the untapped potential in people with disabilities as a talent pool. Additionally, 80% of disability is completely invisible, which begs the question, what assumptions are we making in our interactions and in our offerings simply because someone's disability isn't hyper visible.

These numbers help to get people’s attention, but not it’s not enough to get their meaningful response. It doesn’t incite action or change behavior. In order to move and motivate people, we need to be exposed to more experiences. I am not suggesting that we need to have had disability touch our lives closely (although that helps and is likely to happen in our lifetime), but rather that we need to have engaged and interacted with someone who has been open about their disability and the challenges they face as a result of the world not being designed in their best interest. This could be in the form of user testing or going into the community to seek out perspective.

It really comes down to learning more stories. Something to be weary of is that once you’ve heard one story around disability or accessibility, you’ve heard just one story. There is not one universal experience of disability. I am often surprised by how complex, multidimensional, and pervasive disability is. It can be visible or invisible, genetic or accidental, temporary or permanent. It might be related to cognitive, psychological, physical, or sensory ability; it may be experienced through a chronic or mental health condition. Still, I think we can make it less “surprising” and more appreciated simply by opening up the dialogue.

Scholars such as Elizabeth Barnes view our current world to be inherently able-ist and thus argue that being “disabled” doesn’t by definition mean having a worse off life. What’s your point of view?

First, I want to acknowledge that I not speaking from a lens of someone who identifies as having a disability. That said, I can share my perspective based on my own observations, discussions, and research. In the literature, there are often two models of disability discussed: the medical model and the social model. The medical model views disability as a problem of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma, or other health condition which requires sustained medical care. The social model views disability as a socially created problem, focusing on the disabling conditions in the environment, wherein challenges experienced by people with disabilities are not inevitable, nor are they exclusively a characteristic of the individual’s “broken” body. I prescribe to a secret option C: the biopsychosocial model, which synthesizes what is true in the medical and social models, without making the mistake each makes in reducing the whole, complex notion of disability to one of its aspects. It creates a coherent view of different perspectives of health: biological, individual, and social. All that to say, I do believe our world is ableist and I do not believe that being disabled constitutes a worse off life; it’s just that our society and culture does not optimize the potential for what one’s quality of life could and should be.

As a related aside, there is a trope perpetuated by our ableist society that equally infuriates me as it does disappoint me. We, as society, often view disability in one of two ways: an object of pity or an object of inspiration. You often see the “heart wrenching” commercials or marketing material that paint disability as some tragic circumstance begging for your charity or some heroic story to applaud and get you motivated. It’s not that either of these are inherently wrong. The problem is that this narrow dichotomy fails to recognize disability as a complex part of the human condition.

Is there a difference in how accessibility is discussed and acted upon in academia versus business?

I’m hesitant to make broad strokes across all academia and business, because there is a lot of great discussion and progress being done in both (and perhaps the most glaring gap is the collaboration between the two). I will say that businesses more easily fall susceptible to the shortcomings of the functional-solutions model of disability. This model looks to technological and methodological innovation to address the functional limitations of disability, rather than the sociopolitical implications. This is a very results and solution-oriented view, which can be very beneficial to the advancement of accessible technology. However, where businesses miss the mark is when it becomes more about creating innovative products for profit and PR, rather than those that are practical or useful. Proposed solutions are often unaffordable to a majority of the target population, which undermines original intent. I admire the businesses that find cost-effective and sustainable ways to innovate in the accessibility space, which I admit is not always a simple feat.

What are the main ways the our perceptions and understanding of accessibility are changing?

Our world is becoming evermore digital and our population is living longer. These two megatrends magnify the importance of accessibility in new technology. If we are designing for our future selves, we should be designing with the realization that disability is an inevitable part of the aging process (nevermind the fact that 80% of people who acquire a disability do so before age 64). With that in mind, I think people, organizations, and businesses are beginning to recognize accessibility as “table stakes” to best serve their consumers. There’s an increasing risk to one’s brand when accessibility is overlooked. One striking indicator is that more organizations are building in accessibility from the start, rather than retrofitting products or systems for compliance. While there is sometimes more upfront investment (or creativity) needed, it often pays dividends in the long term. Treating accessibility as a final feature-add has been compared to constructing a 30-floor building and then acknowledging after the fact that an elevator should have been installed. Fortunately, I think we are beyond this approach.

One point of consideration I’ll make is that even in the intensifying spotlight shining on diversity and inclusion, disability is often left in the dark. This is despite the fact that disability is the largest minority, and an identity that intersects with all other underserved groups. Still, I am hopeful that inclusive practices and universal design will continue to evolve and bring people with disabilities more center stage.

What keeps you up at night?

I would say that it cycles between three nightmares:

Most people who are disabled or aging should be able to live with more agency and independence than they currently do. Our failure to adequately prolong, prepare, and support individuals when they do become dependent on others to perform daily tasks is unacceptable. We need to design the tools, technology, environments and policies that allow people to live independently for as long as possible.

The knowledge that there are all these innovative ideas at the periphery that have yet to be brought into focus because we have systematically excluded people who are disabled from joining the conversation.

Understanding my role in the larger movement for disability inclusion. As an ally and advocate, I am continuously striving to stay humble and self-aware, making sure I give space, rather than take it. Even engaging in this interview gives me pause: am I the one that should be getting the microphone in this kind of conversation?

How have new technologies adapted to accessibility and what is considered the most cutting edge today?

I find the phrasing of this question interesting, particularly the use of the word “adapt.” In most cases it is the human - specifically the individuals with a disability - applying adaptive strategies to be able to interact and use new technologies. However, as the question suggests, emerging and existing technologies have been providing enhancements to become more accessible. One example that stands out to me is virtual reality (VR). One important application of VR has been to simulate different experiences of disability, which can provide moments of insight and empathy for those who do not have a disability. Ironically, much of the VR experience is inherently inaccessible. For example, it can be overstimulating for individuals with different cognitive disabilities, not viewable for individuals who are low vision or blind, or difficult to navigate for those with different motor and physical limitations. Accessibility in VR is still developing. Some enhancements include color and vision adaptations, motion attenuation or magnification for motor and neuromuscular challenges, navigation and memory aids, and neurodiverse management tools. This is a great step in the right direction. Developers will need to continue applying principles of universal design to help mediate the sensory experience and modulate physical controls in order to ensure the future of VR is truly inclusive.

*Note from Ayushi: I find this answer to be ESPECIALLY insightful because two friends and I hold a provisional patent for our VR experience that enables eye tracking to make musical education more accessible for children with muscular dystrophy.

What are the main research trends in more accessible technology today and what is still on the periphery that you think holds a lot of promise?

One trend that really excites me is the focus on public spaces. Continual research is being done on how to make places like museums, transportation, parks, roads, and schools even more accessible. Sometimes there is a flashy allure to advancements in the private sector with a focus on product innovation. While products like the Nike FlyLease are exciting, I find that wide scale advancement in the public sector is just as- if not more- important in making sure individuals with disabilities are able to navigate and contribute to their community. I’m excited to see how the future of smart cities builds accessibility into our social and urban infrastructure.

What do most people get wrong about accessibility?

People might think of accessibility as a separate feature, a detour, even an inconvenience rather than an advantage. The beautiful reality is that accessibility inspires innovation and makes experiences better for everyone. Typewriters, text-to-speech and speech-to-text, remote controls, ramps, curb cuts, closed captioning, velcro, automatic doors, easy grip kitchenware, spellcheck are all examples of inventions inspired or created by people with disabilities. Of course, the pattern is clear: these are tools and products that everyone uses, regardless of their ability or disability.

Take the ramp analogy often used to drive home this point: Imagine a significant snowfall has covered the entryway to a public building. If there is both a stairway and a ramp into the building, which path should we clear first? Logically, we should clear the ramp first because it allows so many more people to enter — not just wheelchair users, but people using walkers, people who cannot easily lift their knees without pain, people pushing carriages, strollers, rolling equipment, or rolling bags, in addition to people who are ambulatory. When this scenario unfolds in real life, what often happens is that we clear the stairs first, only allowing the final group inside. Where else are we sacrificing the universal path for the “standard” one?

If you had a magic wand and can change anything about accessibility, what would it be? Or 10 years from now, what do you want to see happen in the field?

I always want us to be aware of the ways we can make experiences more accessible to more people, but in 10 years I hope that accessibility is not even a specialty anymore because it is just embedded to how we think, build, and create.

Obviously one cannot predict the twists and turns of the future, but 10 years from now from the perspective of today - what do you want to be doing?

After two years of working in the healthcare industry, I have been exposed to and worked to address complex problems across many different markets, businesses, populations, and products; all to improve the quality, affordability, and experience of care. In 10 years, I hope to have deepened my expertise and skill set in behavioral science and accessibility to better address these problems. I believe that when we implement strategies to become more aware of (and therefore minimize) cognitive biases in our decision making around policy and on the frontlines, we can start to remove disparity and create a more equitable healthcare system. Specifically, I hope to explore methods for creating decision making environments and “nudges” to promote better policy design, augment treatment decisions, and motivate healthier behaviors for individuals who are amongst the most vulnerable and complex in terms of care (those with disabilities, the polychronic population, and the aging population).

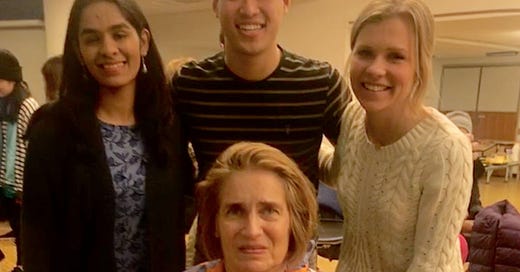

This is me with my friend Helen (my client for the Designing for Disability course)